dailyfieldnotes

Latest posts from Willow's Daily Fieldnotes

-

Resisting a Future of "Write-Nots"

Dec 07 ⎯ Why write at all, when we can use AI to write texts that make sense and may even make us sound smarter than we feel? Last year, the entrepreneur, investor and writer Paul Graham proposed that thanks to AI, we are heading for a world where fewer people write. In a blog post titled Writes and Write-Nots, Graham argued that writing skills have always fallen on a spectrum from good writers to ok ones to people who can’t write. Being an ok writer used to mean facing the pressure and muddling through until you get better. But AI now makes it possible for ok writers not to have to try at all. As a result, Graham continues, in the future, instead of good writers, ok writers, and people who can’t write, there will just be good writers and people who can’t write. What’s the problem? you might ask. Haven’t we always had plenty of people who don’t write? Who cares if we don’t have ok writers anymore? The problem, Graham argues, is that to do certain kinds of thinking, we must write. A world of ok writers outsourcing their writing to AI is a world of people outsourcing their thinking too, making a world with thinks and think-nots. Graham’s blog post finishes: This situation is not unprecedented. In preindustrial times most people's jobs made them strong. Now if you want to be strong, you work out. So there are still strong people, but only those who choose to be. It will be the same with writing. There will still be smart people, but only those who choose to be. But who will choose to write? And why? I am a person who chooses to write. I have written regularly for over 15 years and although I have written over 500,000 words in stories, essays, blog posts and an unfinished memoir, I’ve published little and only recently grew comfortable calling myself a writer. This isn’t uncommon. Even people who’ve published many books struggle with claiming the identity of writer. As poet Maggie Smith wrote in her own blog post about writing titled “What do you do?” this self doubt, or imposter syndrome, leaves a kind of stain that’s hard to scrub out. The antidote? To write regularly. People who garden are gardeners. People who bake are bakers. People who read are readers. People who write are writers. Global creativity maven Julia Cameron echoes this same point in this passage from her book The Right to Write, reflecting on how the act of writing is what makes a writer: 'Did you write today?' 'Yes.' 'Then you’re a writer today.' It would be lovely if being a writer were a permanent state that we could attain. It’s not, or if it is, the permanence comes posthumously. A page at a time, a day at a time, is the way we must live our writing lives. Credibility lies in the act of writing. That is where the dignity is. That is where the final ‘credit’ must come from. How many writers do you know? What about people who journal or blog or write on social media but don’t consider themselves real writers? I know many. I was that person myself for years. Throwback to 2007 when I was starting to figure out I was a creative writer not an academic one. Look at that old Mac (and that baby face)! Working out and being physically stronger has proven health benefits. Even though, as Graham points out, most peoples’ jobs don’t make them stronger anymore, the majority of us understand that exercise makes us healthier. What many people don’t realize: research has also shown that writing contributes to better health. Journaling just 15 minutes per day leads to fewer visits to the doctor over time, and better mental health outcomes. Multiple studies have shown this since the 1980s. So writing isn’t just good for our thinking. It’s good for our mental and physical health. Would more people write if they understood its health benefits? What barriers exist to getting started? I believe the way we define “writer” poses a barrier to getting more people writing. To make a world where more people write—and therefore, as Graham argues, more people think—we need to make more space in the identity of writer. It needs to be as easy to claim the identity of writer as it is to claim the identity of gardener. I plant lettuce and flowers in pots on my balcony, therefore I’m a gardener. I write in my journal, therefore I am a writer. I blog, therefore I am a writer. I have essays or stories in progress, therefore I am a writer. What do you think? Do you feel comfortable claiming the identity of writer? Why or why not?

-

The Smallest Possible Writing Practice

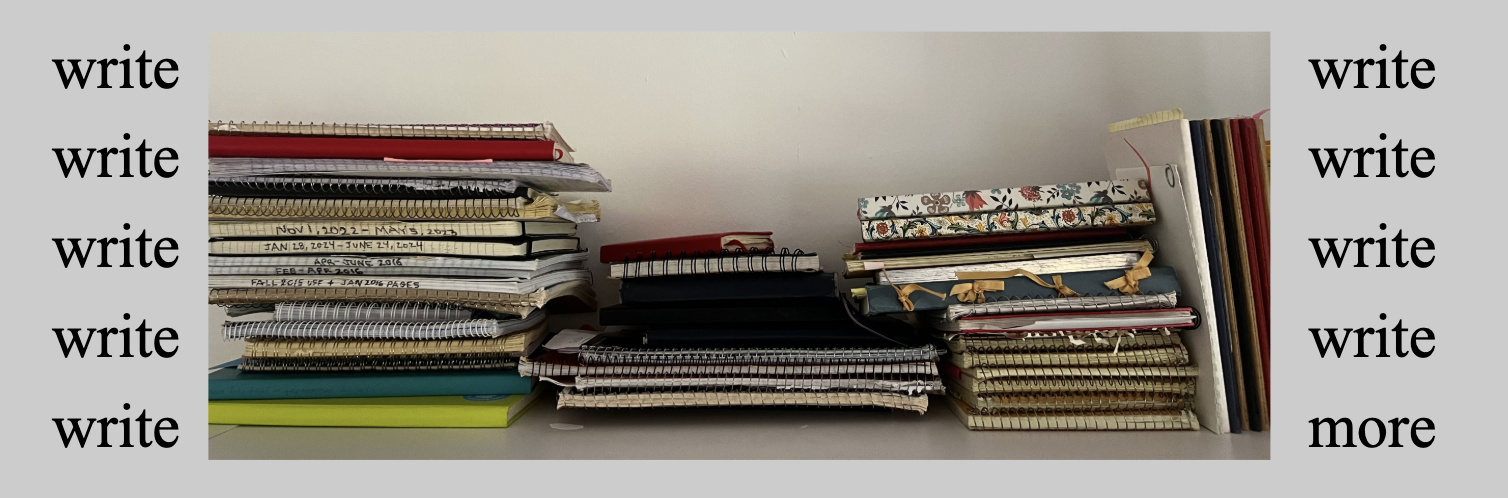

Dec 01 ⎯ Let’s build a habit that stays! wrote the Fika team in their blog post announcing the 4-Week Writing Challenge that introduced many of us to the platform. And looking at the best-of posts from Week 1 and Week 2/3, it’s obvious that while new bloggers in 2025 come from different backgrounds and write about different things, we share one desire: to write more. To build a writing habit. For a lot of people, writing is like exercise, or eating better. An intention they carry around like a smooth stone in their pocket. Maybe they used to journal and stopped. Maybe people keep telling them, You should write about that. Or maybe they’re just curious to be in dialogue with their own thoughts instead of scrolling through life consuming what other people think. We all have goals we return to again and again. Writing is one of them. But it turns out there are a lot of ways to get stuck when you’re trying to write, and building a habit that stays can feel harder than convincing a toddler to put their shoes on mid-tantrum. You tell yourself to focus, turn off notifications, just focus. Then, finally, you do—only to end up staring at a blank page, doubting yourself, unsure where to begin. I am here to tell you another way to start writing. A method so simple that if you already do some version of it, you may not even realize it’s a method. And if you don’t, you’ll find it the simplest thing in the world to begin. Step 1. Notice Where Your Attention Goes To build a writing habit, you need to cultivate a noticing habit. You need to notice when something sparks a thought in your mind that stands out. To be aware when an article you read reminds you of something else you read last week. To notice when a smell brings you back to your first job; or a song to your first love. Notice things, and value that noticing as something unique to you. Specific to you as a person. In the noisy world we live in, it’s really easy to let things blur together. To let your attention jump from one thing to the next. But if you want to write, the road to having a unique voice is paved with noticings—small stones of lived experience that become the foundation of your writing voice. American writer Pam Houston calls them glimmers. Ethnographers call them jottings. They’re tiny, often goal-less moments of awareness that say: Something about this feels different. Pay attention. For instance, I am a person who notices color. My insides sing at the way fall leaves paint the world with yellow. I notice how the gingko trees all turn in a uniform splash as if they’d been dunked in yellow paint while the elms are a patchwork of green and gold as they turn slowly. All the sunshine is in the trees and in piles along the ground this time of year, I jotted down recently while out walking on a gray November day. Which brings me to the other half of the practice. Step 2. Record Your Noticings Writing them down is what turns random noticings into material for writing. Where you capture them doesn’t matter as long as you can a) keep it with you at all times and b) easily return to it later. I’ve kept notebooks much of my adult life, and I always carry one in my purse. But my noticing habit only turned into a more consistent writing habit when I started using the Notes app on my phone, and taking photos related to the noticings. You might record voice notes to yourself. Text yourself in WhatsApp as a design friend does. Or write by hand on index cards you carry in your pocket the way Austin Kleon and Anne Lamott do. In my experience, worrying too much about finding the right method can derail the practice. Instead, let yourself simply try something for a week. If it doesn’t work for you, try something else. The point is to start noticing what you notice, and to capture it in a consistent place. A Story: One Word Can Be a Practice Once upon a time a woman with three young kids and a demanding job took a writing class. She wrote for 15 minutes a day for two months, even extending the practice with classmates afterward. She was finally writing consistently the way she’d long wanted to do. She felt more alive than she had in a long time. But when the group ended and the holidays arrived, she stopped writing. On New Year’s Eve, while cooking dinner with a writer friend, she confessed how impossible it felt to keep writing amid the fullness of her life. What if you start small? Her friend said. A writer they both admired had been blocked during Covid and gave herself permission to write one word a day and call it a writing practice. What if you try that? The idea seemed so beautifully simple. Why not? the woman thought. She opened a new Note in her phone and called it One Word Can Be A Practice. The next day, January 1, 2022, she listed her New Year’s intentions in the Note, starting with 1. Write at least one word a day. That woman was me, and that was nearly four years ago. I quickly found I couldn’t write just one word because my brain always wants to finish the thought. But promising myself it could be just one word made possible to keep writing, no matter how life-y life got. Amazingly, when I moved the Note into a Google Doc at the end of 2022, I discovered I’d written 40,763 words. An average of 111 words a day. And every year since then I’ve written more. The One Word Note for 2025 already surpasses 75,000 words—487 of which include the initial idea for this post. Try Living in the World as a Person Who Writes Are you someone who loves gardens? Takes pictures of flowers? Stops to pet every dog you pass? Or are you someone who obsesses about politics? Watches the news religiously? When you’re at a party, what stands out to you? When you flop down on the couch at the end of the day and zone out watching Instagram reels, what makes you laugh the most? Or are you a person who scrolls and feels nothing but anger? To write, you have to notice what you notice. To believe that the experience you’re having is unique AND universal. That what you notice and think about can have meaning not only to you, but to the broader culture you’re a part of. Choose a tool. Start small. Be consistent. If you’re like me, it won’t feel like much at first, and you might even feel silly stopping to note things down. But over time you will find that one word—one noticing—at a time can become a way to live in the world as a person who writes. Otherwise known as building a writing habit that stays.

-

Raising Humans in the Age of ChatGPT

Nov 21 ⎯ It’s funny that Daddy likes AI and you don’t, my eight-year-old daughter says, looking over my shoulder as I add photos and links to my first Fika post, What AI Can’t Know. Her comment surprises me. Why do you say that? She bounces next to me on the couch. Because Daddy talks about ChatGPT all the time and you don’t. You think? My concentration broken, I consider what she’s just said. Do I dislike AI? Is liking or not liking it even the right question? Where is she getting this idea? I look out the window over her shoulder and watch a flock of swallows taking off from the neighbor’s pine tree. Impatient, she leans in. I try to explain my opinion in terms she can understand. It’s not that I don’t like AI and Daddy does. It’s that he’s more excited about everything it CAN do and sometimes needs to remember its limits. And I think it’s important not to forget all the parts of being a person that ChatGPT ISN’T very good at, and to make sure we’re not losing connection with those. She stands up, says again, It seems like you don’t like it. Then, it’s on to the next thing now that she has Mama’s attention. I close the laptop, resigned that finishing the post later, and watch her leap from couch to couch, startling our cat who was fast asleep. It shouldn’t surprise me that my eight-year-old has an opinion like this. After all, her dad is an AI early adopter—someone who was experimenting with AI-based software in 2016, long before most people had heard of ChatGPT. For the last three years, hardly a day has passed without him showing us something new. The images it can make! The code it writes! The videos now! The voice explanations for your questions! As a designer and researcher, I’m as pleased as anyone when AI automates a dull task that I used to do by hand. Like having Notebook.LM spit out interview transcripts minutes, versus the dozens of tedious hours I spent transcribing my Catalan and Spanish dissertation interviews 15 years ago. Or quickly exploring logo ideas before committing to the slow work of making them in a design tool. But I use it with caution. I ask questions about its utility for learning. To use it well, you need judgment, the knowledge to know what you’re asking for and to see when the information is wrong. And as a designer of learning experiences, I’m concerned about how to cultivate that. What is appropriate use when you aren’t an expert? What’s the path from novice to expert in the age of AI? How do we mentor people along that path? Who supports people, if everyone is turning to ChatGPT for advice? Especially life advice. Did you know that in 2025, the top use case for GenAI is therapy and companionship. Yes, the very one I wrote about last week is number one, according to an infographic published by Harvard Business Review earlier this year. Number 2 and 3? Organize your life and Find purpose. As Marc Zao-Sanders writes in the full study: GenAI is not merely a tool for efficiency but is increasingly becoming an integral part of human decision-making, creativity, and emotional support. Let’s just pause a moment on this. What does it even mean to get emotional support from a computer? What about the so-called loneliness epidemic? What will that look like in 10 years when today’s kids are becoming adults? In 30 years when their kids are in school and having problems on the playground? I find the eight-year-old writing in her notebook while listening to a podcast. My turn to interrupt her. Do you think AI can help you when you feel mad? Her answer is immediate. NO, it’s digital and has no feelings. She looks at me like I know nothing. Her sister, reading across the room, joins in. It wouldn’t help AT ALL. It literally has NO feelings. She goes on, perfectly imitating the generically helpful voice of the Google. When I say, ‘I’m so angry at you!’ it’s been like, ‘I’m so sorry, I hope I can make it up to you in some way.’ I decide to keep going. How about creativity? Is AI creative? The eleven year-old, now fully part of the conversation, jumps right in. Kind of? But it doesn’t really get things right. I asked it to make a picture of flying cats, and some of the cats didn’t even have wings! My third kid, a teenager, is doing homework at the dining table near us. What do you think? I ask him. Can AI be creative? He considers, his mind on Geography and History. I guess? It can make images. But is that real creativity? I press him. This is fun, and I want the conversation to keep going now. You ask deep questions, he replies, and goes back to his homework. Indeed I do, and you should too.

-

What AI Can't Know

Nov 14 ⎯ There’s nothing quite like the pleasure of a midday Sunday coffee at the end of a weekend away with friends. The richness of two days spent laughing, talking, thinking, imagining. Three pairs of hands wrapped around warm cafes con leche. Jackets we pull tight against the autumn air. A question, a topic, a world of ideas to explore before we part ways. What do you think of using ChatGPT for life advice? I know someone who’s going through a breakup and told me they talked with ChatGPT for five hours recently, and that they felt they really got to the core of understanding some of their issues. I have opinions, says one friend. Me too, lots. And off we go into the vast possibility of deep, curious conversation between friends. We talk about the risks of giving personal information to the tools. The cost of maintaining the data centers. The probability that soon there will be advertising based on what people are sharing in these seemingly private chats. Imagine you are asking ChatGPT for advice because you’re fighting with your sister, and the AI suggests you should go visit her, says our most critical friend. Then you go to Kayak to look at tickets and the prices can be manipulated, because the tools now know how important it is for you to travel to the place where your sister lives. Damn, I say. You’re so right. The targeting that’s possible when you’ve catalogued someone’s innermost thoughts is far beyond the cookies that currently sell us things based on our search history. Plus most of these tools are housed in the US, where profits matter far more than protecting people. (Just look up the Zuckerberg hearings around the negative impact of social media on teenage girls if you need an example.) But it’s not all politics and dystopian futures. We also get philosophical. How is AI impacting our sense of self? Can a generative AI really know anything at all? How is it possible that a tool built to model relationships between words—a tool that has no real knowledge of its own—is helping people understand themselves? And what does it mean for a human brain to know things, really? Brain research tells us that different sides of the brain are responsible for different parts of who we are, I offer. I’ve been reading Conscious: A Brief Guide to The Fundamental Mystery of the Mind by Annaka Harris and the research she shares about how the two sides of the brain work is completely fascinating. In the vast majority of people, Harris writes, the left hemisphere is responsible for the expression of language through speech and writing, leaving the right hemisphere mute; however, the right hemisphere is able to communicate through nodding and gestures of the left hand (and singing, in some cases.) AI is trained on written knowledge; information collected and passed on and reproduced by left brain language. What about all the parts of human experience happening in the right brain? And what about the fact that we don’t even understand many ways of knowing including how our emotions and nervous system interact, let alone have them documented enough to be included in AI models? We leave without answers—but with the rock-solid certainty that this conversation is better than any we might have with ChatGPT. That living in bodies that can drink coffee and hear the crunch of autumn leaves under our feet as we hug each other goodbye is essential to being human.